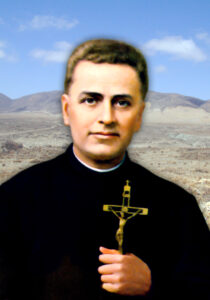

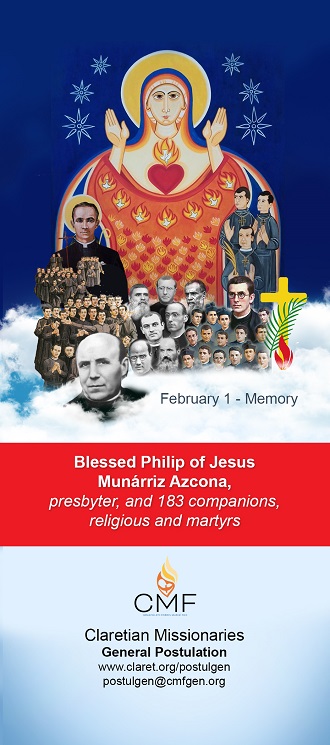

The year advances until October of this emblematic 2024, in which we are commemorating the 120th anniversary of the Easter of the Venerable Fr. Mariano Avellana and the 175th anniversary of the Claretian Congregation. And in this month so distinctly Claretian we cannot fail to value the charism that the holy Founder impressed with fire in the soul of Mariano and led him to his missionary dedication to the point of surrendering his life in it. Without this vital impulse it would have been impossible for his enlightened son to evangelise without rest in the American frontier that he had just come to know; and that he did it in the midst of enormous physical sufferings and until he fell dead in the last of his hundreds of missions.

A country of contrasts

One of its great writers called Chile a ‘crazy geography’, noting that in addition to being the second longest and narrowest country in the world, it has almost every possible climate, from its desert ‘northern gate’ to the Antarctic glaciers, and from the Andes Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Nevertheless, its enormous social contrasts – which, with varying levels and nuances, have endured throughout its almost 500 years of history – constitute an almost permanent element of tension which, in the 31 years of Mariano’s tireless apostolate, was particularly acute.

A mining and agricultural country par excellence, this second characteristic was the most extensive until well into the 20th century. Although extractive mining contributed an essential part of the national treasury from Mariano’s time onwards, subsistence agriculture and the poor exploitation of the land in huge estates that concentrated great poverty and a feudal landlord system, lasted for a long time. In the meantime, state-driven industrialisation was gaining ground and consolidating in a way that became exemplary in Latin America.

A transcendental inflexion point opened up precisely when Mariano set foot on chilean land in 1873: in the enormous area of the Bolivian-Chilean-Peruvian Atacama Desert, the world’s largest concentration of a product that was then very valuable both for agricultural fertilisation and for the manufacture of explosives in the military industry had been discovered: saltpetre, a mixture of sodium nitrate and potassium nitrate, which, together with other minerals, was extracted from the mines in a concentrate called caliche.

The control and benefits of the whole productive system – as well as the political management – by the national elites were then concentrated in Santiago and a few other important cities. As a result, the poor and hungry peasants increasingly converged on them, until they formed huge belts of misery, disease, desolation and death around the relatively developed and affluent centres.

Mariano’s mission field

This was the reality that Mariano Avellana faced as soon as he set foot in Santiago, where the Claretian missionaries had arrived only three years earlier to make Chile the first country where they would manage to consolidate themselves outside their native Spain and begin to spread throughout America.

Inspired by the charisma of the Founder, his sons had accepted to settle precisely in one of the most miserable and abandoned sectors of the emerging capital of the country. Fully committed to this reality, the missionaries not only evangelised a very poor population, mostly illiterate, with men enslaved by alcoholism, and with the consequent family violence. They also distributed food, taught how to produce food and natural medicines in the absence of medical services, set up a school, and soon began construction of a church dedicated to the Heart of their Mother, which would eventually become the first Basilica of the Heart of Mary in the world.

From this primary location, Father Mariano went out on mission to the parishes, farm chapels and fields in the surrounding area. Little by little he extended his radius of action, travelling on horseback, in wagons, on foot, in the first trains that plied the country, or in the holds of old cargo ships.

Sneaking into the slums where overcrowding, squalor, pestilence and suffering of all kinds prevailed, he ‘combed more than 1,500 kilometres across the country, missioning without rest. Although a very painful herpes eroded his belly for 20 years until his death, in the midst of which he burst a wound in his leg which, far from healing, grew to the size of an open hand and accompanied him until he died. However, he never mentioned these problems, did not slow down his pace of work because of them, and even continued to ride through the fields and mountains of the crazy Chilean geography.

Bloody Caliche

The ambition for saltpetre sparked international greed and conflict between the three producing countries. Six years after Mariano’s arrival, in 1879 Chile embarked on an armed conflict against Peru and Bolivia, paradoxically known as the ‘War of the Pacific’, which was more accurately known as the ‘Saltpetre War’. Chile emerged triumphant and annexed the Desert regions that had previously been Peruvian and Bolivian. Today they are the largest in the country and the richest in mineral resources.

As a consequence, a ‘white gold rush’ sowed the desert with saltpetre mines, thousands of kilometres of railways, and an unprecedented concentration of workers, who gradually crowded into them with their families.

The exploitation capital was supposed to be Chilean, but the state privatised the operations in order to obtain high taxes for the fiscal coffers, and so the so-called ‘Oficinas Salitreras’ ended up in the hands of mainly English and other countries’ capital.

The enormous social contrasts, injustices and labour abuses that had prevailed in the traditional farms were repeated and increased. So much so that wages were not paid in money, but in tokens exchangeable for food and essential products only in stores called ‘pulperías’ owned by the same employers, who, with honourable exceptions, thus committed abominable usuries.

But the enormous development of the mining industry also became a new field of evangelisation for the sons of Claret, and especially for Father Mariano. Residing for many years in the communities opened in La Serena and Coquimbo, some 480 km north of the capital, he travelled to the minerals located in the area of Copiapó – today’s Atacama region – and further north, in Antofagasta. Despite the fact that irreligiousness, drunkenness, debauchery, prostitution and abuse of women reigned there, the man known as the ‘Apostle of the North’ raised his powerful voice everywhere to shake consciences, rectify courses, recompose families and Christianise environments.

Nevertheless, social injustice led to great tragedies. Father Mariano was already dead when, in 1907, workers from various saltpetre offices went on strike and, with their wives and children, descended en masse from the mines in the Andes Mountains to the management in the port of Iquique, some 1,800 km north of Santiago, to demand better wages and better work. They gathered at the Santa Maria School, and were soon joined by other unions, until the port was virtually paralysed.

Faced with government orders from Santiago, military forces ordered the strikers to vacate the school and leave the city. When they refused, men, women and children were mercilessly gunned down. According to the government, 126 people were killed. But various sources put the death toll at between 2,200 and 3,600. The exact figure has never been clarified.

Alfredo Barahona Zuleta Vice-postulator, Cause of V. Fr. Mariano Avellana, cmf