Apr 7, 2025 | From the martyrs, Mariano Avellana

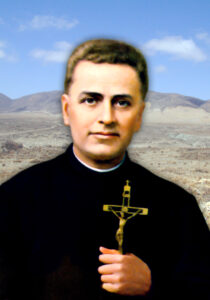

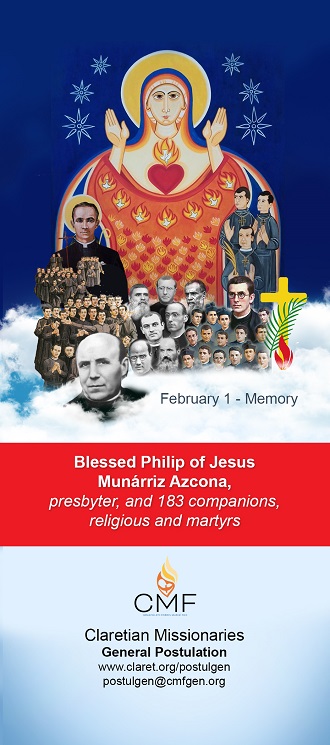

The international Claretian family concluded on December 31, 2024, the commemoration of the 120th anniversary since its distinguished missionary, Mariano Avellana Lasierra—recognized as the greatest evangelizer of Chile between 1873 and 1904—gave his life in a mining camp in the north of the country, a life he had vowed to dedicate especially to the sick, prisoners, and the most abandoned.

How could we not see in this the greatest proof of love, which, according to Christ Jesus, consists in laying down one’s life for those whom one loves?

For many years now, February 14 has been consecrated as the Day of Love, and primarily, the Day of Lovers. Centuries ago, it was attributed to Valentine, a Roman physician and devout priest, that he protected and married couples despite an imperial ban by Emperor Claudius II, who believed that marriage was incompatible with a military career. For such disobedience, Saint Valentine is said to have been martyred on February 14, around the year 270. Regardless of these traditions, the date ultimately came to be dedicated, almost by definition, to the celebration and experience of romantic love.

However, beyond the fact that commerce and profit have distorted the true meaning of such a sublime celebration, love itself has become one of the most corrupted and degraded realities. Instead of understanding love as self-giving, even to the point of laying down one’s life for the beloved, it has been turned into a right of possession, domination, and even annihilation and murder of the one who, having supposedly been loved, became deeply hated.

It is no mere coincidence that the 14th of each month, dedicated by the Claretian family to remembering the heroic testimony of love of Mariano Avellana, this February coincides with the Day of Love. Rather, it can be seen as a singular opportunity to show both believers and non-believers his complete testimony of true love. As a beautiful song says: “To love is to give oneself, forgetting oneself, seeking what may make the other happy. How beautiful it is to live to love; how great it is to have in order to give; to give joy and happiness, to give oneself—this is love!”

That Mariano Avellana loved to the point of heroically giving his life was recognized by Pope John Paul II when he declared him Venerable in 1987. His life bore witness to this, in the tireless way he evangelized Chile for 30 years amidst great suffering and hardship, dedicating himself especially to the sick, the prisoners, and the most abandoned. And he did so until he fell, exhausted to death, during the last of his hundreds of missions.

He had not forgotten Christ’s commandment on the eve of His death: “Love one another as I have loved you.” Nor the emphatic words of John, His beloved disciple: “Whoever does not love has not known God, because God is Love. Whoever claims to love God but hates his brother is a liar. How can someone love God, whom they have not seen, if they do not love their brother, whom they have seen?”

And just as Christ loved His friends to the point of giving His life for them, Mariano set out to give his own life in the farthest reaches of an unknown continent to which he had been sent to mission. And he fulfilled it.

Alfredo Barahona Zuleta

Oct 22, 2024 | From the martyrs, Mariano Avellana

The year advances until October of this emblematic 2024, in which we are commemorating the 120th anniversary of the Easter of the Venerable Fr. Mariano Avellana and the 175th anniversary of the Claretian Congregation. And in this month so distinctly Claretian we cannot fail to value the charism that the holy Founder impressed with fire in the soul of Mariano and led him to his missionary dedication to the point of surrendering his life in it. Without this vital impulse it would have been impossible for his enlightened son to evangelise without rest in the American frontier that he had just come to know; and that he did it in the midst of enormous physical sufferings and until he fell dead in the last of his hundreds of missions.

A country of contrasts

One of its great writers called Chile a ‘crazy geography’, noting that in addition to being the second longest and narrowest country in the world, it has almost every possible climate, from its desert ‘northern gate’ to the Antarctic glaciers, and from the Andes Mountains to the Pacific Ocean.

Nevertheless, its enormous social contrasts – which, with varying levels and nuances, have endured throughout its almost 500 years of history – constitute an almost permanent element of tension which, in the 31 years of Mariano’s tireless apostolate, was particularly acute.

A mining and agricultural country par excellence, this second characteristic was the most extensive until well into the 20th century. Although extractive mining contributed an essential part of the national treasury from Mariano’s time onwards, subsistence agriculture and the poor exploitation of the land in huge estates that concentrated great poverty and a feudal landlord system, lasted for a long time. In the meantime, state-driven industrialisation was gaining ground and consolidating in a way that became exemplary in Latin America.

A transcendental inflexion point opened up precisely when Mariano set foot on chilean land in 1873: in the enormous area of the Bolivian-Chilean-Peruvian Atacama Desert, the world’s largest concentration of a product that was then very valuable both for agricultural fertilisation and for the manufacture of explosives in the military industry had been discovered: saltpetre, a mixture of sodium nitrate and potassium nitrate, which, together with other minerals, was extracted from the mines in a concentrate called caliche.

The control and benefits of the whole productive system – as well as the political management – by the national elites were then concentrated in Santiago and a few other important cities. As a result, the poor and hungry peasants increasingly converged on them, until they formed huge belts of misery, disease, desolation and death around the relatively developed and affluent centres.

Mariano’s mission field

This was the reality that Mariano Avellana faced as soon as he set foot in Santiago, where the Claretian missionaries had arrived only three years earlier to make Chile the first country where they would manage to consolidate themselves outside their native Spain and begin to spread throughout America.

Inspired by the charisma of the Founder, his sons had accepted to settle precisely in one of the most miserable and abandoned sectors of the emerging capital of the country. Fully committed to this reality, the missionaries not only evangelised a very poor population, mostly illiterate, with men enslaved by alcoholism, and with the consequent family violence. They also distributed food, taught how to produce food and natural medicines in the absence of medical services, set up a school, and soon began construction of a church dedicated to the Heart of their Mother, which would eventually become the first Basilica of the Heart of Mary in the world.

From this primary location, Father Mariano went out on mission to the parishes, farm chapels and fields in the surrounding area. Little by little he extended his radius of action, travelling on horseback, in wagons, on foot, in the first trains that plied the country, or in the holds of old cargo ships.

Sneaking into the slums where overcrowding, squalor, pestilence and suffering of all kinds prevailed, he ‘combed more than 1,500 kilometres across the country, missioning without rest. Although a very painful herpes eroded his belly for 20 years until his death, in the midst of which he burst a wound in his leg which, far from healing, grew to the size of an open hand and accompanied him until he died. However, he never mentioned these problems, did not slow down his pace of work because of them, and even continued to ride through the fields and mountains of the crazy Chilean geography.

Bloody Caliche

The ambition for saltpetre sparked international greed and conflict between the three producing countries. Six years after Mariano’s arrival, in 1879 Chile embarked on an armed conflict against Peru and Bolivia, paradoxically known as the ‘War of the Pacific’, which was more accurately known as the ‘Saltpetre War’. Chile emerged triumphant and annexed the Desert regions that had previously been Peruvian and Bolivian. Today they are the largest in the country and the richest in mineral resources.

As a consequence, a ‘white gold rush’ sowed the desert with saltpetre mines, thousands of kilometres of railways, and an unprecedented concentration of workers, who gradually crowded into them with their families.

The exploitation capital was supposed to be Chilean, but the state privatised the operations in order to obtain high taxes for the fiscal coffers, and so the so-called ‘Oficinas Salitreras’ ended up in the hands of mainly English and other countries’ capital.

The enormous social contrasts, injustices and labour abuses that had prevailed in the traditional farms were repeated and increased. So much so that wages were not paid in money, but in tokens exchangeable for food and essential products only in stores called ‘pulperías’ owned by the same employers, who, with honourable exceptions, thus committed abominable usuries.

But the enormous development of the mining industry also became a new field of evangelisation for the sons of Claret, and especially for Father Mariano. Residing for many years in the communities opened in La Serena and Coquimbo, some 480 km north of the capital, he travelled to the minerals located in the area of Copiapó – today’s Atacama region – and further north, in Antofagasta. Despite the fact that irreligiousness, drunkenness, debauchery, prostitution and abuse of women reigned there, the man known as the ‘Apostle of the North’ raised his powerful voice everywhere to shake consciences, rectify courses, recompose families and Christianise environments.

Nevertheless, social injustice led to great tragedies. Father Mariano was already dead when, in 1907, workers from various saltpetre offices went on strike and, with their wives and children, descended en masse from the mines in the Andes Mountains to the management in the port of Iquique, some 1,800 km north of Santiago, to demand better wages and better work. They gathered at the Santa Maria School, and were soon joined by other unions, until the port was virtually paralysed.

Faced with government orders from Santiago, military forces ordered the strikers to vacate the school and leave the city. When they refused, men, women and children were mercilessly gunned down. According to the government, 126 people were killed. But various sources put the death toll at between 2,200 and 3,600. The exact figure has never been clarified.

Alfredo Barahona Zuleta

Vice-postulator, Cause of V. Fr. Mariano Avellana, cmf

Jul 30, 2024 | From the martyrs, Mariano Avellana

Mariano Avellana, considered the greatest evangelizer in more than 150 years of history of the Claretian missionaries in the confines of America, is an especially propitious opportunity to project his figure to the present. In this way, we can imagine with what messages and actions he would travel thousands of kilometers today, in comparison with those he once carried through Chilean soil, in the more than 700 missions, spiritual exercises, and deep reflections that, with abnegation and “heroic” sufferings, he preached for more than 30 years; especially to the sick, the imprisoned and those most neglected by society.

Mariano, tireless in his desire to Christianize the unknown country where he felt sent to become “either a saint or dead,” raised his voice and sought to transform, in accordance with the Gospel and the reality of his time, the religious impiety, situations of sin, injustice, and enormous abuses against the weakest that he encountered there. He did not cease to do so until he fell dead in the last of his missions.

Mission in today’s world

Today’s realities are certainly very different from those of the past. A globalized world has opted mainly for an environmentally destructive development model at a level that is driving the human species to the brink of extinction. In the midst of it, situations of misery, abuse, or persecution have unleashed massive migrations of desperate beings who, in pursuit of the mirage of abundance, perish by the thousands in the ocean or are prevented from entering modern-day Jaujas, suffering, abuse, and death. Can we suppose that Mariano Avellana would keep silent about this in his exhausting missionary journeys?

Wouldn’t dozens of endemic wars that nobody cares about, and new ones that do make the news because of the magnitude of their horrors and possible escalation, which could lead to a global conflict of unimaginable consequences for the whole of humanity, fall within the demands for awareness and coherent action that Mariano would claim as the primary obligations of Christians today?

The innumerable cases of abuse, injustices, and humiliations of the weakest that prevail in the economy, work, and other areas of personal and social relations today, as well as the violations of essential rights, whether to life, integrity, health, food, fair wages, housing, education, protection of children, of abused and murdered women, of the discarded elderly and so many other realities, would they not be pressing issues for the word and action of the distinguished disciple of Claret who was Mariano Avellana?

We cannot think that he would remain impassive and would not demand that Christians “make trouble,” as Pope Francis urges him to do. Even less would he remain silent in the face of more than 36,000 dead, mostly innocent women, children, and the elderly, over 78,000 wounded, 1,500,000 displaced at gunpoint, and more than 70% destruction of the entire infrastructure of the Gaza Strip, a substantial part of the land where the Son of God pitched his tent and wished peace countless times.

Nor would it do the same in the face of the war between Russia and Ukraine, which dates back at least 10 years and, in the last two years, has resulted in more than 80,000 deaths.

An example that questions and demands

We can only guess how he would guide his missionaries in the face of these and other scourges of our world today. But knowing how he approached his world in word and deed, it is possible to infer what kind of missionary Mariano Avellana would be today.

120 years after his death, it is worthwhile not only to reflect on it but, above all, to extract the example that his figure offers to the whole Claretian family, religious and laity, men and women, for whom his passage through the earth is not a mere model to contemplate but a demanding paradigm of missionary life and action according to the full charism of Anthony Mary Claret. This was the source from which Mariano drew inspiration to be the distinguished missionary that we long to see on the altars, as a testimony of what it means to be a missionary “who burns in charity, burns wherever he goes and seeks by all means the glory of God and the salvation of human beings.”

Alfredo Barahona Zuleta

Vice-postulator, Cause of Ven. Fr. Mariano Avellana, cmf