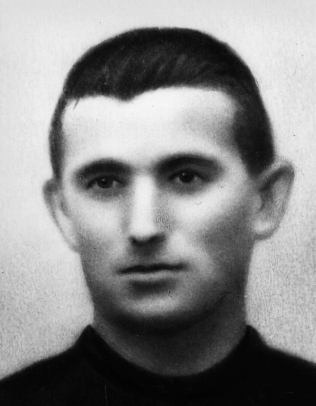

Theology student

23 years old

Born in Miralcamp (Lérida) on 4 October 1912, he showed a marked attraction to prayer and recollection from an early age.

He first entered the diocesan seminary in Solsona and then the Claretian seminary in Vic.

He took his religious vows on 15 August 1929. The continuation of his career was made difficult by the law on military service and the special circumstances.

Already in 1931 he sensed the danger and wrote home: ‘As for the present situation, we live by the day. We put ourselves in God’s hands because anything can happen’.

‘We are serene,’ he wrote in December 1934, ‘amid the uncertainty that reigns everywhere and can turn things upside down from one day to the next’.

He had been living in Barbastro since August 1935; at the time of his imprisonment, he had just finished his theological studies.

He realized that political events were precipitating and, addressing his family in December of the same year, he said: ‘On these elections depends on the life or death of Spain and perhaps even of Religion’.

Two months later he spoke of the electoral fraud perpetrated by the Left, which did not prevent the narrow victory of the Right in Barbastro.

In June 1936, he heard the revolution beating at the gates and told his relatives: ‘Here there is peace, for now, thank God. Personally, we have not suffered any rudeness or annoyance, although they have forbidden the ringing of bells and have taken over the bishop’s seminary to ruin it. Unfortunately, this is how revolutions go…

Small in stature, lively, and susceptible; it cost him no small effort to come to self-mastery.

He ended his earthly adventure, giving his life for Christ, on 13 August 1936.

His final words are of abandonment in God: ‘May your divine will always be done, O Lord!

FATHER CLARET AND THE PRESS

No one is unaware that almost all of the irremediable evils that modern society deplores have their origin in this libertine press which, under the title of freedom and progress, is inoculating poison into souls and crumbling the edifice of society.

And since it is also true that to prevent the efficacy of a poison, it is necessary to counteract it with a counter-poison, we would like to remember, by extolling his memory, that apostolic man who did so much to inflict it on the society in which it was his lot to live. Let us speak of Venerable Fr. Anthony Ma Claret, for whom the Church is preparing in these days the supreme honour of the altars. Whoever doubts this affirmation has only to take a quick glance at his work, which no one else has equalled, as a popular writer, and he will be sufficiently convinced that it is difficult to find anyone in the 19th century who has done as much Catholic propaganda, by means of the press, as Claret, and that hardly any rival will be found in this sense in the preceding centuries.

If we wanted to give in a few words a general idea of what he wrote, we would say that he wrote about apologetics, morals, asceticism and mysticism, the arts and sciences, oratory and agriculture. In particular, there was no branch in the ecclesiastical subjects about which he did not write something. But note that we consider as pamphlets those writings that do not exceed l60 pages. It is true that he is not the original author of some of them, but he has translated them or improved them in such a way as to make them almost his own. But it is difficult to appreciate the merit and the work that so much writing entails if one does not take into account the continuous and very serious occupation that overwhelmed him, which, had it not been for Fr Claret, would have made it materially impossible for him to write anything. He had no choice but to steal time from sleep. Many wise and virtuous people, among them the Rmo. Orge, the former General of the Dominicans, could not explain so much activity except by divine intervention.

Not content with having written so much and on so many different subjects, he encouraged others to do the same, and not infrequently he himself paid for their printing. But his greatest work, in this point of Catholic propaganda, is the foundation of the Religious Bookshop and the Academy of St. Michael; works, according to the mind of the founder, destined exclusively to flood society, which groans under the weight of so many bad books and pamphlets, with a deluge of good books.

If figures are the best panegyrist, we have to say that the Religious Bookshop alone from 1848, the date of its foundation, to 1866 printed 2,811,100 volumes of various sizes: 2,509,800 pamphlets and 4,249,200 catechism posters and leaflets. Total: 8,569,800 printed. More than half a million per year. From 1879 to 1902 he printed one million six hundred and seventy thousand.

In less than nine years of existence of the Academy of St. Michael, it distributed 1,734,000 books free of charge, corresponding on average to 120,000 per year: 1,734,004 prints, 25,311 medals, 2,112 crucifixes and 10,201 rosaries. In addition, 20,396 books were lent, and an infinite number of loose sheets and pamphlets were distributed. If Fr. Claret, in all his life, had done nothing more than found the Religious Bookshop and the Academy of St. Michael, he would seriously deserve to have a monument erected to him as an Apostle of the Catholic press. And what shall we say if we consider that the greater part of these writings are his own work? he number of volumes of his own books and pamphlets is known to exceed 6,000,000 souls out of 150 editions that are known and whose number of copies we do not know. And what about the flyleaves, whose editions were much more numerous? The printing house of Aguado alone, in Madrid, published 280 in a short time, which added to those brought out by the Librería Religiosa give the figure of 4,723, 280 copies. And it is noteworthy that almost all these sheets bear allegorical prints, drawn by the Servant of God himself. Other bookshops published works by Father Claret which were to be added to the figures already given. What writer in such a short time has ever been able to see such a prodigious number of copies of his works?

And don’t think that all this was driven by a desire for profit or fame, no, but rather that he was the first to pay the printing costs and distributed them all for free. He himself states that in 1863 he left the Librería Religiosa 4,000 duros. In Cuba he distributed more than 200,000 books. On the trips he made with the kings in Spain, he had arranged that in each city where they stopped he would find a box of books to distribute. In the trip he made through southern Spain in 1862 alone, he distributed more than 85 arrobas of books (“arroba” = 12,4 kg), pamphlets and leaflets.

To conclude: if the great Catalan poet Verdaguer could truly say that “The indefatigable Apostle of Catalonia had been the first, most active and most popular propagandist that the Catalan press had in his century”, we must similarly say of the Apostle of the Canary Islands, of Cuba, of the whole of Spain; for with equal zeal he exercised his apostolate in them, that giant soul, for whose enterprises the world was small.

You must be logged in to post a comment.