Jesus, you know,

I am your soldier:

Always by your side

I will fight.

With you always

And till I die

One flag

And an ideal.

And what ideal?

For You, my King,

The blood to give…

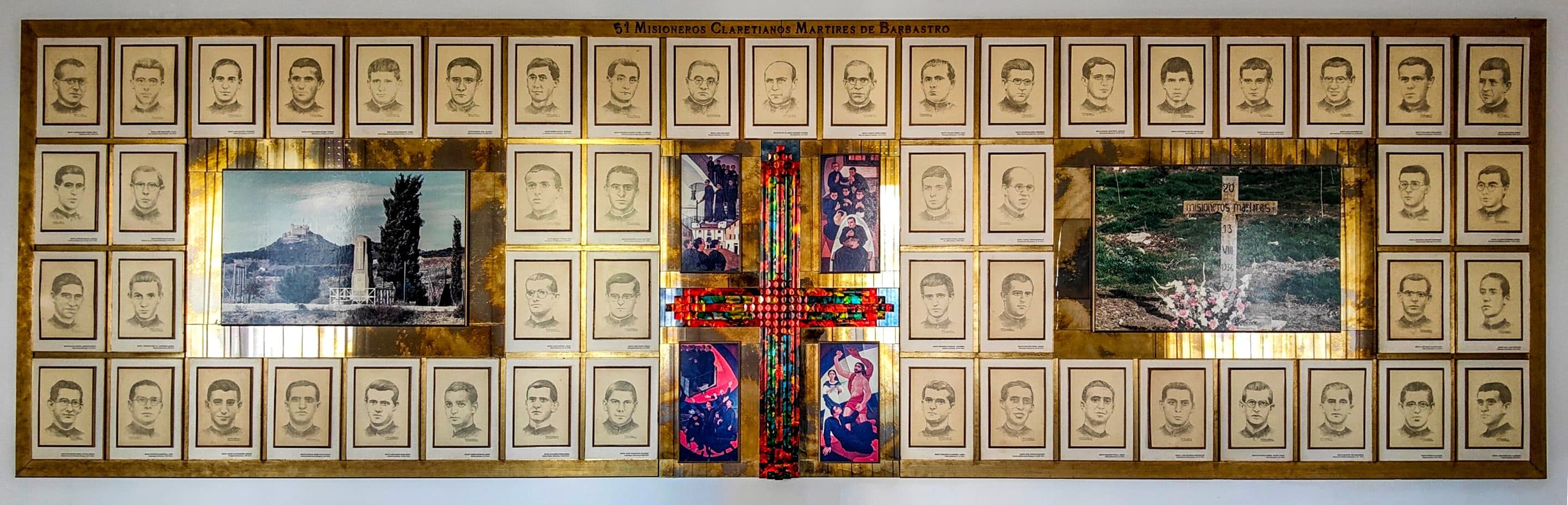

The martyrdom of the 51 Missionaries Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, Claretians, of Barbastro took place during the month of August 1936, at the beginning of the Spanish Civil War.

The affirmation repeated by the militiamen that it was enough for the missionaries to abandon their religious activities to save their lives points to a hostility not against the individuals but against what they represented, the faith, the Church. “We do not hate your persons,” they were told; “what we hate is your profession.” “We are killed only because we are religious,” some of these martyrs wrote.

The Claretian Community of Barbastro was formed by 60 missionaries: 9 Priests, 12 Brothers, and 39 Seminarians about to receive priestly ordination.

On Monday, July 20, 1936, the house was assaulted and searched, unsuccessfully, for arms, and all its members were arrested.

The superior, Fr Felipe de Jesús Munárriz, the formator of the seminarians, Fr Juan Díaz, and the administrator, Fr Leoncio Pérez, were taken directly to the municipal prison. The elderly and sick were taken to the asylum or the hospital. The others were taken to the Piarist school, where they were imprisoned in the auditorium until the day of their execution. Their passage through the streets of Barbastro was like a procession; witnesses remember the religious, “as if they were returning from communion”, and this was indeed the case, for before leaving the house, they had all received communion.

During their short stay in prison, the three leaders of the Claretian community were truly exemplary: they never complained, they encouraged their co-prisoners and sacrificed themselves for them, they prayed intensely for themselves and their persecutors, and they went to confession and confessed to other prisoners. Without any kind of judgment, simply because they were priests, they were killed at the entrance to the cemetery at sunrise on the second of August.

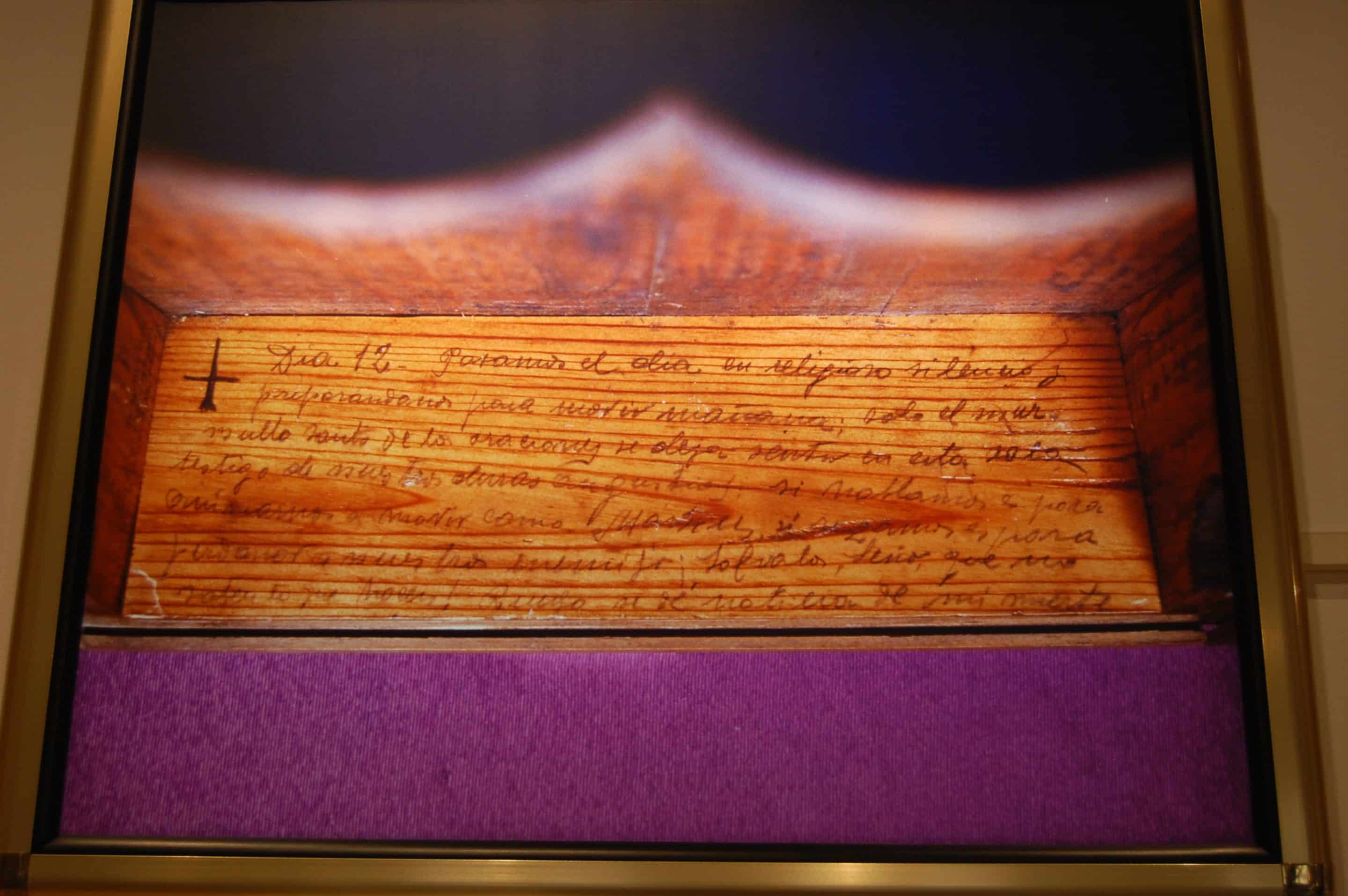

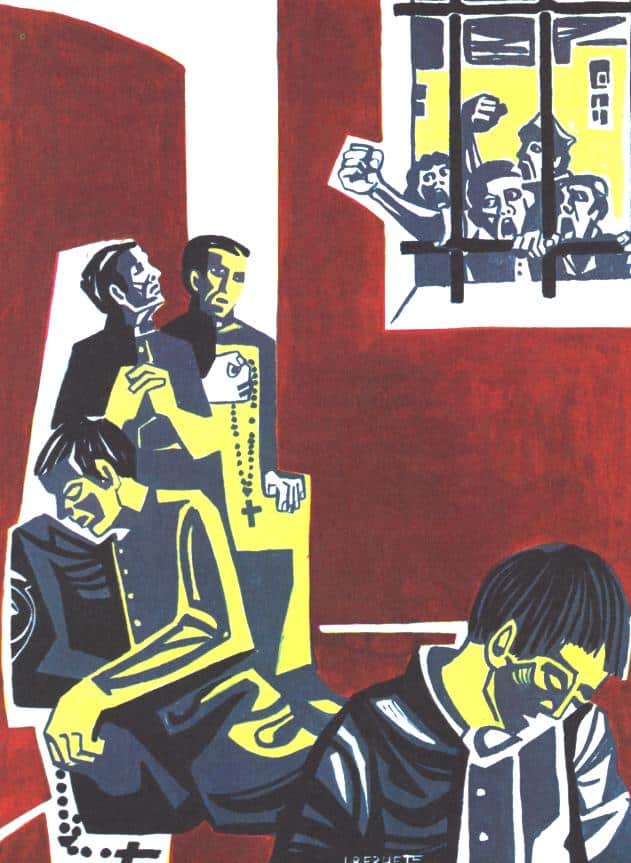

The prisoners in the Piarist Hall prepared to die from the first moment: “We spend the day in religious silence and preparing to die tomorrow; only the holy murmur of prayers can be heard in this room, the witness of our hard anguish. If we speak, it is to encourage us to die as martyrs; if we pray, it is to forgive; save them, Lord, for they know not what they do,” wrote one of them.

During the first days of imprisonment, they were able to receive communion secretly, and the Holy Communion was the center of their life and the source of their courage. Prayer, the recitation of the Office of the Martyrs, and the Rosary prepared them for death.

They had to endure the inconveniences of prison, but above all, the rationing of water in the middle of summer. They were tortured with execution simulations: “more than four times we received absolution believing that death was upon us, “testifies Parussini, one of the two Argentinean Claretians, imprisoned with the others and released on 12 August because he was a non-national. “One day, we spent almost an hour without moving, waiting for the next moment to be shot.”

Prostitutes were brought into the hall to provoke them, with the threat of immediate executions if they did not comply. But not even one of them gave in. Nor were the offers of liberation that several of them received from the militiamen any good: they preferred to follow the luck of their companions and die martyrs like them.

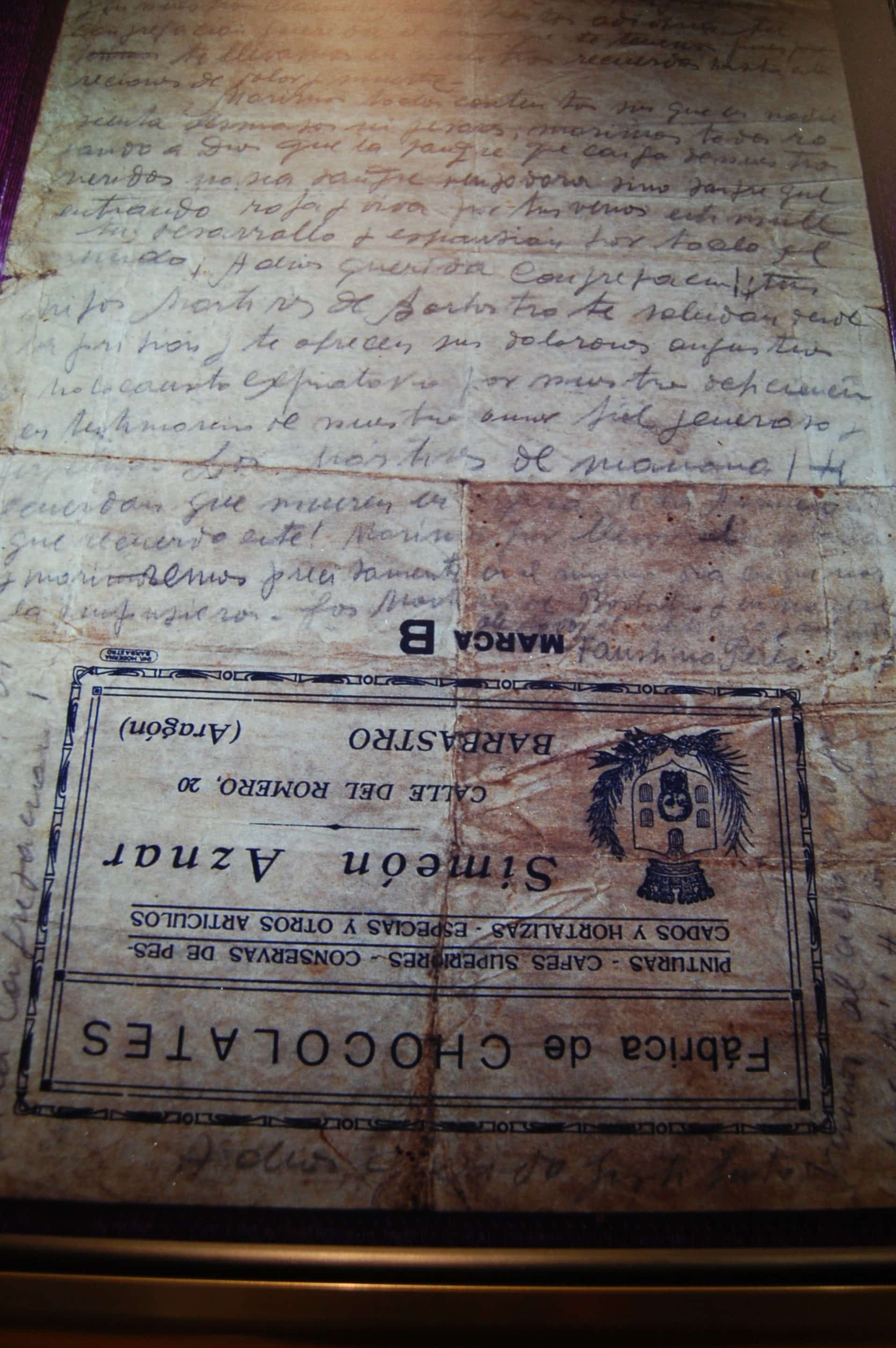

They were convinced that they were going to be martyrs. One of them wrote to his relatives on 10 August: “The Lord deigns to place in my hands the palm of martyrdom; on receiving these lines, sing to the Lord for such a great and significant gift as martyrdom, which the Lord deigns to grant me… I would not exchange prison for the gift of working wonders, nor martyrdom for the apostolate which was the desire of my life.” From the 12th are these other testimonies of his joyful martyrdom consciousness: “With my heart overflowing with holy joy, I confidently await the culminating moment of my life, martyrdom”; “just as Jesus Christ on the height of the cross expired forgiving his enemies, so I die a martyr, forgiving them with all my heart”; “we all die happy for Christ and his Church and the faith of Spain”; “do not cry for me; Jesus asks me for my blood; for His love, I will be a martyr, I will go to heaven.” These are some of the writings that they stamped on small pieces of paper, on chocolate envelopes, on the walls, and on a piano tabouret.

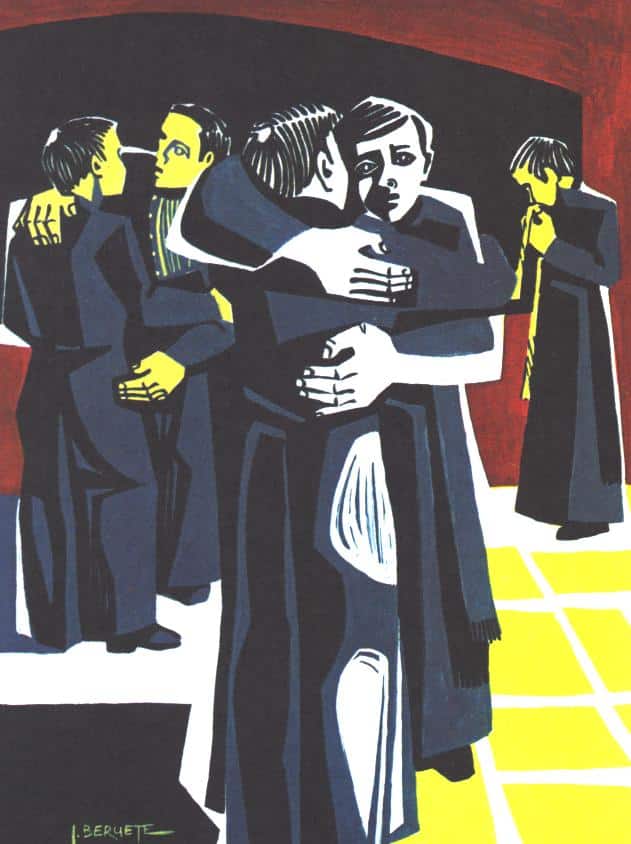

They went in groups to martyrdom on different days. The first group, in the early morning of the 12th, was made up of the six elders, Fathers Sebastián Calvo, Pedro Cunill, José Pavón, Nicasio Sierra, the subdeacon Wenceslao Mª Clarís and Brother Gregorio Chirivás. They responded without any resistance to the call of their executioners; they tied their hands behind their backs, and two by two, they were tied together side by side. Father Secundino Mª Ortega, from the stage, gave them absolution. “At seven minutes to four”, they heard from the hall the shots. Before shooting, the militiamen offered them, for the last time, the possibility of apostasy, but they remained faithful to the end.

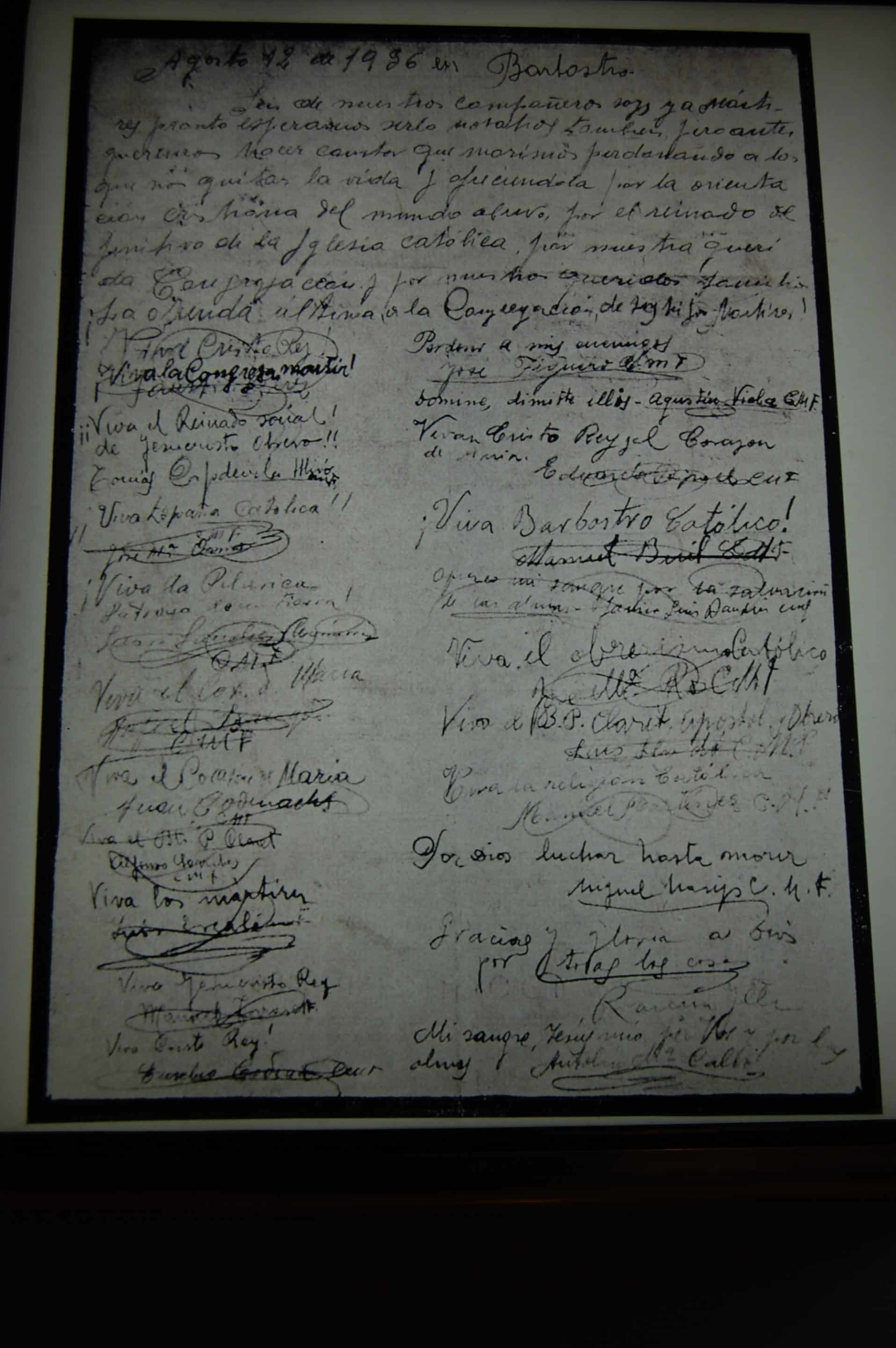

From that moment on, those who were there began to prepare themselves “soon and fervently for death.” They wrote and signed “the last Offering to the Congregation of their martyr sons”: “August 12, 1936. In Barbastro. Six of our companions are already Martyrs; soon we hope to be so too; but first, we want to state that we die forgiving those who take our lives and offering them for the Christian orientation of the working world, for the definitive kingdom of the Catholic Church, for our loved Congregation and our dear families.”

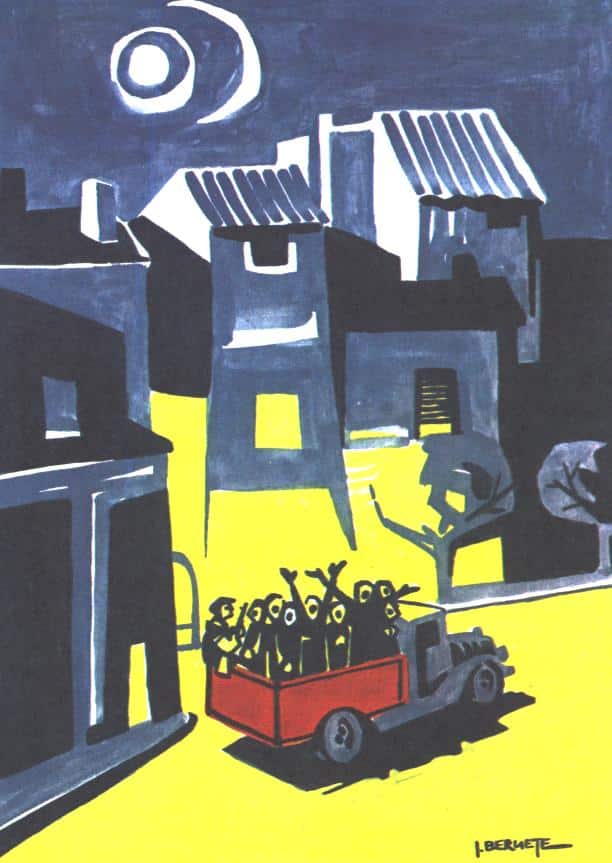

The following night, “when the cathedral clock struck twelve”, the militiamen entered the hall. As there was no one over twenty-five years old, they read out a list of twenty names: Fr. Secundino Mª Ortega, the students Javier Bandrés, José Brengaret, Antolín Mª Calvo, Tomás Capdevila, Esteban Casadevall, Eusebio Codina, Juan Codinachs, Antonio Mª Dalmau, Juan Echarri, Pedro García Bernal, Hilario Mª Llorente, Ramón Novich, José Ormo, Salvador Pigem, Teodoro Ruiz de Larrinaga, Juan Sánchez Munárriz, Manuel Torras; and Brothers Manuel Buil and Alfonso Miquel. Nobody faltered or showed cowardice. Father Luis Masferrer, the only priest left, gave them absolution. Those who remained saw them get into the truck; they heard them crying out to the King Christ and singing hymns that expressed the ideal of their missionary life. At twenty to one in the morning of the 13th, the shots of the firing squad and the shots of grace were clearly heard.

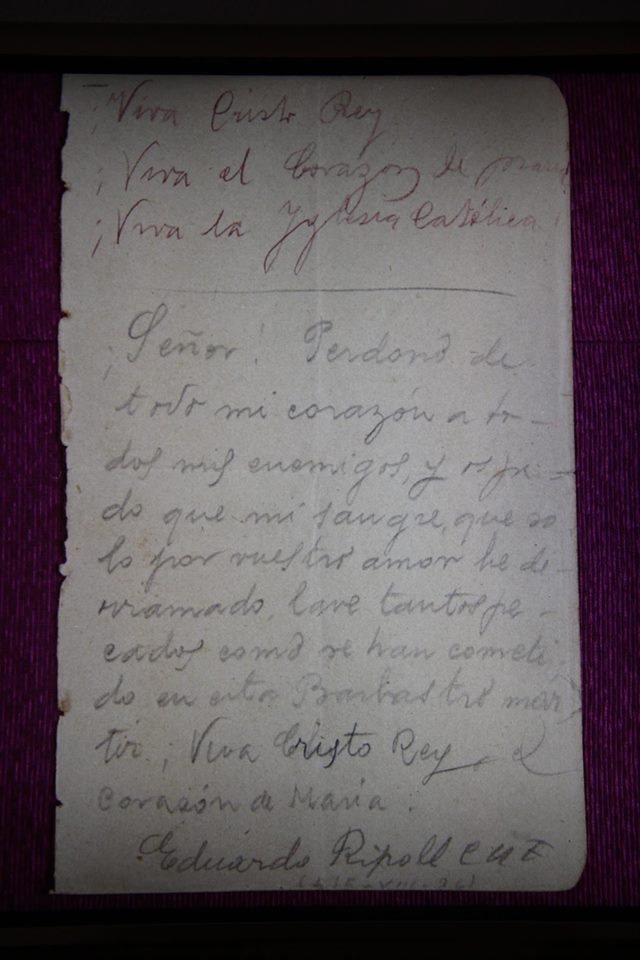

The last 20 were taken to martyrdom at dawn on the 15th, Assumption of Mary, the anniversary of the Profession of the majority, Fr. Luis Masferrer, the students José Mª Amorós, José Mª Badía, Juan Baixeras, José Mª Blasco, Rafael Briega, Luis Escalé, José Figuero, Ramón Illa, Luis Lladó, Miguel Masip, Faustino Pérez, Sebastián Riera, Eduardo Ripoll, José Ros, Francisco Mª Roura, Alfonso Sorribes and Agustín Viela, and Brothers Francisco Castán and Manuel Martínez Jarauta.

Earlier, they wrote what can be considered their testament: “Dear Congregation, the day before yesterday six of our companions died with the generosity with which martyrs die; today, the 13th, 20 have received the palm of victory, and tomorrow, the 14th, we hope that the remaining 21 will die. Glory to God! We spend the day preparing ourselves for martyrdom and praying for our enemies and our dear Institute. When the time comes to designate the victims, there is a holy serenity in everyone and anxiety to hear their names, to go forward and place ourselves in the ranks of the chosen ones; we await the moment with generous impatience, and when it has arrived, we have seen some kiss the ropes with which they were tied, and others address words of pardon to the armed rabble: when they go by truck to the cemetery, we hear them crying: Viva Cristo Rey! … Tomorrow the rest of us will go, and we already have the motto to acclaim, even if the shots ring out, the Heart of our Mother, Christ the King, the Catholic Church and you, the common Mother of all of us. … We all die happy … we all die praying to God that the blood that falls from our wounds will not be avenging blood, but the blood that, flowing red and alive through your veins, will stimulate your development and expansion throughout the world.”

The two young seminarians, Jaime Falgarona and Atanasio Vidaurreta, who had been hospitalized as sick, were called after midnight on the 18th and confessed to a prisoner priest. Together with several other priests and lay Catholics, they were brought, without judgment, to martyrdom.

The recognition of their heroism in the face of martyrdom was acknowledged from the first moment by the city of Barbastro and the Claretian Congregation. It was very clear, both in the testimony of their martyrdom and in their writings, their passionate and unreserved love for Jesus Christ, their filial devotion to the Heart of Mary, their joyful and committed belonging to the Church and to the Congregation, their deep love for their families and their desire for reconciliation and forgiveness for those who took their lives. Heirs of the apostolic spirit of St. Anthony Mary Claret, they had been attentive to the missionary challenges of their time, they had shown themselves sensitive to the most disadvantaged of their time, the workers, and they were preparing themselves with enthusiasm and a universal view for a future ministry.