The year was 1921. After the end of the World War, plague and famine raged among the Russian population, especially in the south and newborns and the elderly. Pope Benedict XV raised his voice to alert the whole world to the tremendous tragedy descending on those lands. Aid had begun to arrive when death surprised the Holy Father. It was Pius XI who, in his eagerness to ensure that the aid arrived safely and wishing to give a testimony of presence, in his Letter Annus Fere to the Bishops of the whole world, communicated to them that “for the greater efficacy and fruit of this charity, the collections, and distribution of alms must be made in an orderly and correct manner, It is up to our diligence, venerable brothers, to gather these, according to the opportunity of the circumstances, and they, once collected, will be taken by men of our choice wherever the need is most urgent and distributed among the neediest without distinction of nationality or religion.“

Indeed, the news of the famine in Russia was tragic. In a Report of the Pontifical Mission of Aid to Russia, they went so far as to write: “the conditions are extremely distressing. For example, in some small villages in Western Crimea, especially in the localities called Tupabash, Tupkinegah and Terklinabash on the Sea of Azof, the starving people have begun to boil their shoes to make a kind of leather soup. The scenes in the hospitals where the sick and dying are piling up are particularly depressing. The lack of health aid and the minimum of hygiene is unbelievable, if unseen.“

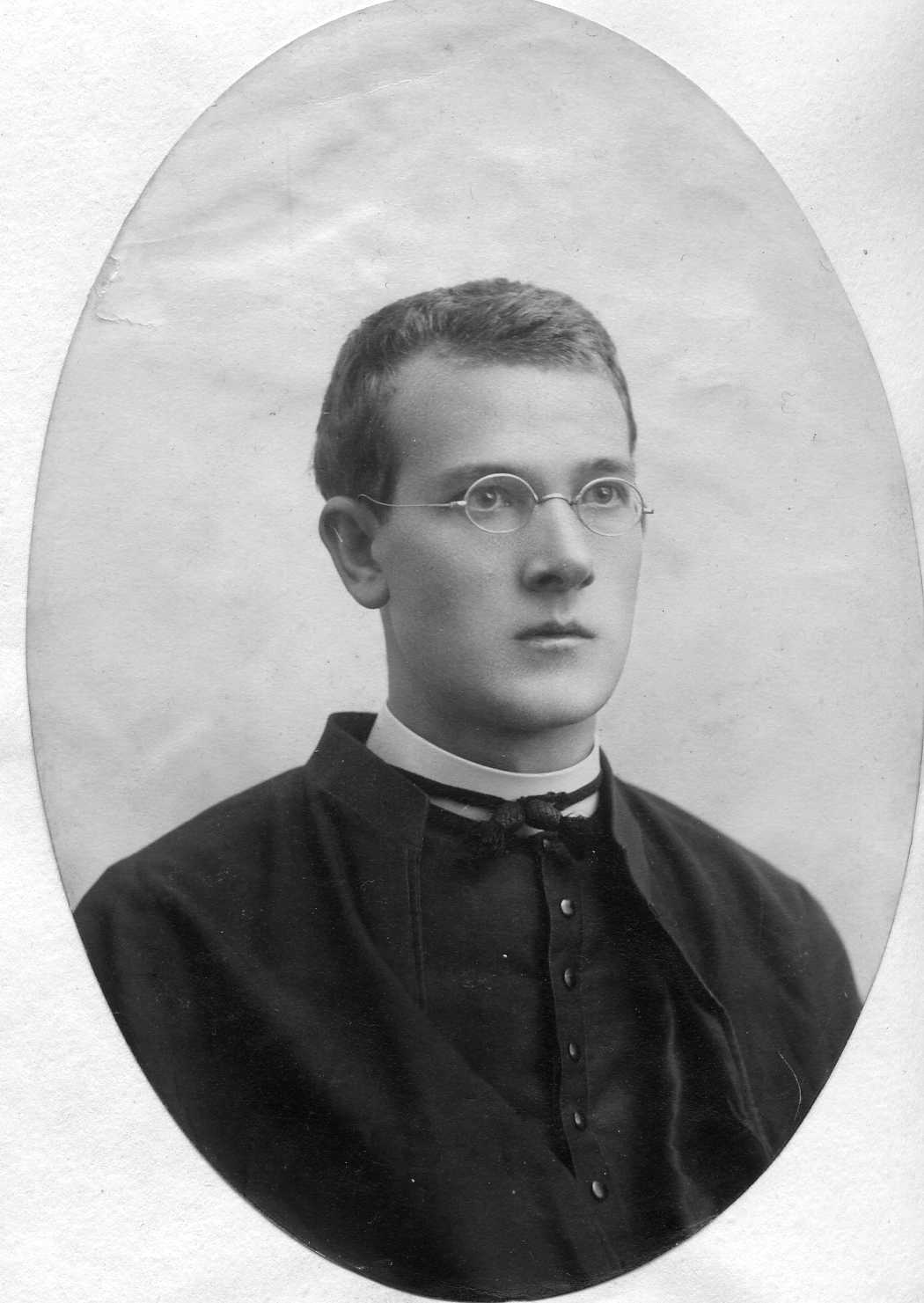

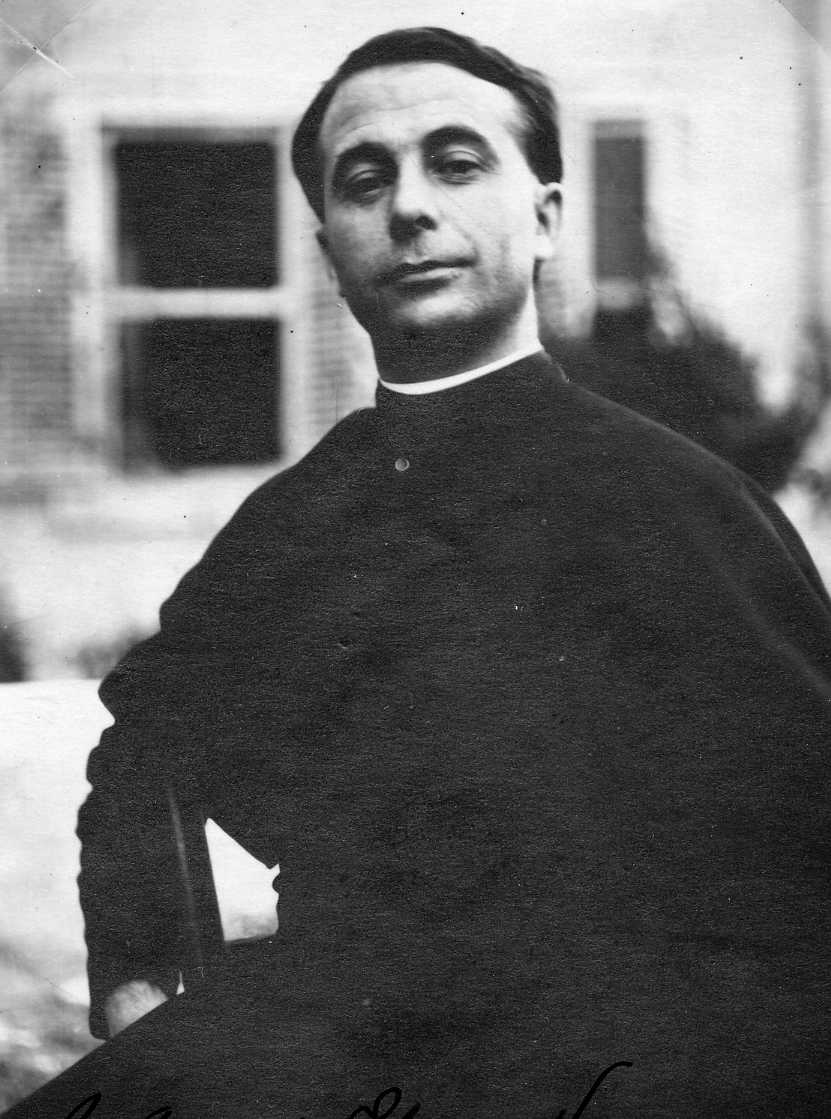

When the time came to choose those the Holy See chose, the religious congregations willing to carry out this difficult and painful mission were considered. Among them were the Claretian Missionaries. The other three were the Jesuits, the Salesians, and the SVD. The Claretians selected were Frs. Pedro Volts, as the person in charge, and Ángel Elorz.

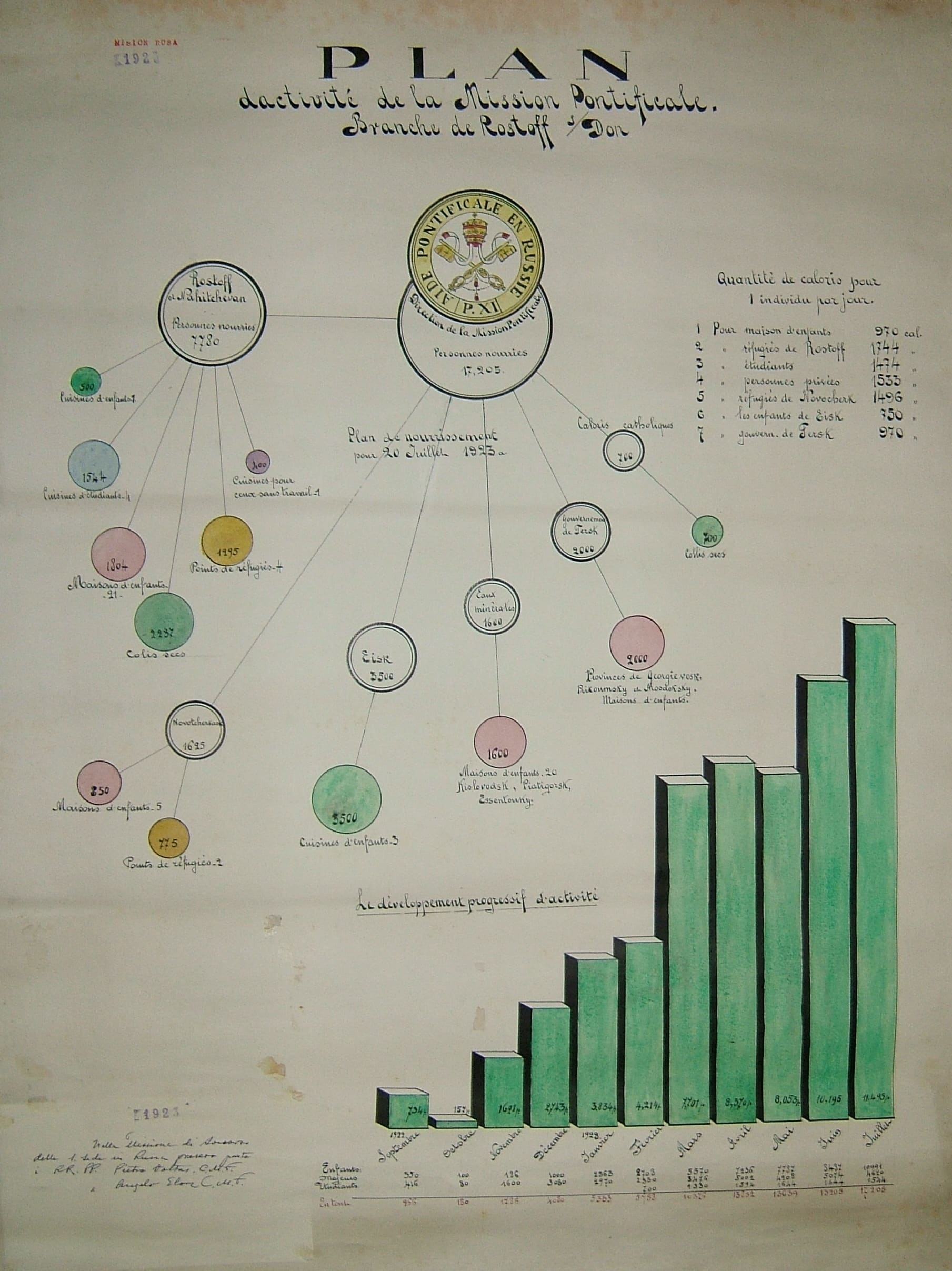

On July 24, 1922, they embarked on the steamship Galicia to cross the Adriatic, the Gulf of Otranto, the Ionian Sea, and the Gulf of Lepanto on their way to Istanbul. On August 2, they set sail for the Bosphorus and the Black Sea, as far as the city of Odessa. Father Voltas describes the image of that beautiful ancient city: “It lay before our eyes like a gigantic cemetery or like the habitation of walking skeletons. Scrawny children who slipped away from the vigilance of those who looked like soldiers judging by the rifle they carried approached us saying in Russian, ‘Sir, give me some bread, I am hungry‘”. From there, after a couple of days, they took the train that in 24 hours took them to Rostoff na Donu, their destination. This was where the inhabitants of the Volga basin, fleeing from hunger, as well as those from the Kouban area and the Caucasus, had ended up. The overcrowding of fugitives, starving, and sick people were enormous. Before the world war, it was a commercial city, thanks to fishing and agriculture.

As soon as they arrived, they began an unstoppable activity collaborating with the Italian Red Cross and the American Relief Administration, which at that time were starting to evacuate their troops from the area. The description of what they found there verges on the Dantesque. “People, especially children, wrapped in rags, lay on the sidewalks sighing from cold and hunger. The most horrible thing is that in Rostoff, before our arrival, there were unbelievable cases of cannibalism. Children were caught in the dark of night, and after slitting their throats, they were put in salt to be eaten. It was common to feed almost exclusively on sunflower seeds, an abundant plant in Russia for oil production.” Soon the newspapers focused their attention on the enormous work of these missionaries, reproducing testimonies and letters. Despite a particular conflict that arose in the relationship between the two missionaries, the work of Fathers Voltas and Elorz had gone ahead without being influenced by their personal situation.

In the middle of 1923, the task of the Claretian Missionaries commissioned by the Holy See in Russia came to an end. At the beginning of July, Cardinal Gasparri called the two to Rome. On October 16, Fr. Nicolás García received a communication from the Secretariat of State that said: “While Fathers Pedro Voltas and Ángel Elorz leave their work in Russia, where in the name of the Holy See they exercised one of the most precious missions of charity, His Holiness wants me to send to Your Most Reverend and to all the members of the meritorious Institute that you worthily preside, the clear testimony of His magnificent complacency and His paternal gratitude in the two excellent religious, who were so happy to fulfill the difficult duty with generous dispositions of sacrifice and love, the Holy Father had the satisfaction of contemplating a new proof of the excellent Christian spirit of which the Institute is animated. And from this spirit, hoping for the good of souls and the very prosperity of Your Congregation, the Supreme Pontiff is happy to confirm his magnanimous benevolence to P.V. and all the brothers. With his heart, he imparts to You, to Frs. Voltas and Elorz, to all the Missionaries Sons of the Immaculate Heart of Mary, the Apostolic Blessing.”

This can be a testimony not only of how the Congregation has always been involved in the human tragedies of the times, despite its weaknesses, but also of the open and available attitude it has been able to maintain throughout its history to respond to the most urgent needs, at the right time and effectively.